DES MOINES, Iowa — A bill in Iowa that could result in the state arresting and deporting certain migrants is causing worry among immigrant communities, leading some to ask themselves: “Do I need to exit Iowa?”

The bill, which is anticipated to receive approval from Gov. Kim Reynolds, would establish it as a state offense for a person to be in Iowa if they were previously denied entry to or removed from the United States. It reflects a portion of a Texas law that is presently blocked by the court.

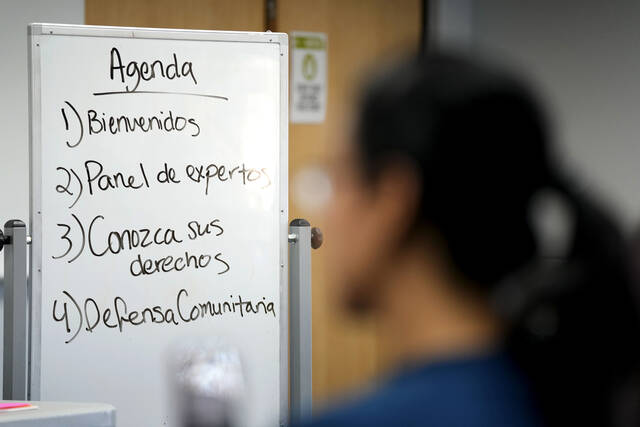

Throughout Iowa, Latino and immigrant community organizations are arranging informational gatherings and materials to address people’s inquiries. They are also requesting official statements from local and county law enforcement agencies, as well as in-person meetings.

During a recent gathering of 80 individuals in a community room at a public library in Des Moines, community organizer Fabiola Schirrmeister randomly selected written questions from a container. One question in Spanish was: “Is it safe to call the police?” Another asked: “Can Iowa police question me about my immigration status?” And: “What happens if I’m racially profiled?”

Erica Johnson, executive director of Iowa Migrant Movement for Justice, the organization hosting the meeting, sighed when someone posed the question: “Should I leave Iowa?”

“Entiendo el sentido,” she said. I understand the sentiment.

Schirrmeister, who has a local Spanish-language radio program, explained the extensive efforts organizers have made to establish a connection with law enforcement.

“It’s regrettable how it will damage the trust between local enforcement, pro-immigrant organizations, and the immigrant communities,” she remarked.

Des Moines Police Chief Dana Wingert stated in an email to The Associated Press that immigration status does not influence the department’s work to ensure community safety, and he expressed that it would be “disingenuous and contradictory” to include it while law enforcement has been working to eliminate such prejudice.

“I’m not interested, nor are we equipped, funded or staffed to take on additional responsibilities that historically have never been a function of local law enforcement,” he added.

In Iowa and across the country, Republican leaders have united around the assertion that “every state is a border state” as they accuse President Joe Biden of neglecting his duties to enforce federal immigration law. This has prompted Republican governors to send troops to support Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s Operation Lone Star, and legislatures to propose a variety of state-level strategies.

Iowa’s lawmakers pushed the measure to tackle what one lawmaker described as a “clear and present danger” posed to Iowans by some migrants crossing the southern border. Republican Rep. Steve Holt acknowledged concerns about the constitutionality of the bill but ultimately contended that Iowa has “the right, the duty and the moral obligation to act to protect our citizens and our sovereignty.”

“If we end up in a court battle with the federal government, should this pass, bring it on,” Holt said during a subcommittee meeting in February. “I think it’s time for every state to stand up and say … ‘we’ve had enough. We will defend our people.’”

The Texas law is stuck in court after being challenged by the U.S. Department of Justice, which says it clashes with the federal government’s immigration authority. The department did not immediately comment on the Iowa bill.

The Iowa law, like the Texas law, could lead to criminal charges for individuals with outstanding deportation orders or those who have been previously removed from or denied entry to the U.S. Once in custody, migrants could either comply with a judge’s order to leave the U.S. or face prosecution.

The judge’s order must specify the method of transportation for leaving the U.S. and a law enforcement officer or Iowa agency to oversee the departure of migrants. Those who refuse to leave may be re-arrested on more serious charges.

The Iowa bill encounters the same issues of implementation and enforcement as the Texas law, as deportation is a “complex, costly and often risky” federal process, according to Huyen Pham, an immigration law expert at Texas A&M School of Law.

“How will Iowa law enforcement agencies determine if someone has entered Iowa in violation of an immigration order?” Pham questioned. She pointed out remaining uncertainties about the destination country for a detained person, the means of transportation, and communication with those countries.

Deportations involve two countries, she explained, so state-by-state disjointed immigration policy could jeopardize international relationships, Pham remarked.

Mexico has already stated it would reject any enforcement of immigration laws by state or local government.

The Iowa State Patrol, along with representatives from various police departments and county sheriff’s offices across the state, declined to comment on the bill until it is signed into law.

Shawn Ireland, president of the Iowa State Sheriff’s and Deputies Association and sheriff in Linn County, mentioned in an email that law enforcement officials would seek advice from county attorneys if the bill becomes law.

However, Ireland emphasized that community-police relations are a priority, and law enforcement’s focus “is not on searching for people who came to this country illegally and are not committing crimes.”

Manny Galvez, leader of the Escucha Mi Voz (Hear My Voice) community group based in the rural city of West Liberty, remarked that the bill has energized immigrant communities, including those in harder-to-reach areas of Iowa, to convey the message that immigration is a human issue and that the state’s meatpacking plants, cornfields, and construction projects rely on immigrant labor.

Lawmakers pushing for a bill like this one are disconnected from that reality.

“Criminalizing the immigrant community is not the solution,” he stated. “We tell people: ‘Don’t be afraid. No tengan miedo. We are going to keep fighting this.’”