Last week, conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt interviewed Zach Carter, who is The Huffington Post‘s senior political economy reporter. The interview’s purpose was to discuss Carter’s negative response to Hewitt’s previous interview of former Vice President Dick Cheney. The interview was lively and interesting but it did not go well for Carter, who was forced to admit his ignorance of the historical context of the situation in Iraq.

Looked at one way, the interview might almost seem like pointless point-scoring. In response to Hewitt’s questions, Carter admitted he didn’t know who Alger Hiss was and that he hadn’t read The Looming Tower. Those two questions are standard questions for Hewitt’s interviews.

But then Carter said he hadn’t read various other books, such as Bernard Lewis’ Crisis of Islam, Robin Wright’s Dreams and Shadows, or Thomas P. M. Barnett’s The Pentagon’s New Map. He said he hadn’t read Dexter Filkins’ The Forever War but that he’d “read a lot of the stuff that he’s written for The New Yorker.” Filkins joined The New Yorker in 2011. He said he does not read politician’s memoirs, including Cheney’s or George W. Bush’s. That he was unaware that Bill Clinton had bombed Iraq in 1998 or that Gadhafi had reportedly disarmed in 2003. He admitted he doesn’t know who A. Q. Khan, the father of the Pakistan bomb and godfather of Iranian and North Korean nuclear programs, is.

It’s such a display of ignorance that it seems almost unfair. But looked at another way, it’s simply a good interview where Hewitt seeks to establish Carter’s background and breadth of knowledge in order to help listeners know on what basis he critiqued Cheney.

My favorite line was when Carter was asked if he’d heard of George Weigel and he replied, “I’ve heard of Dave Weigel.”

I don’t mean to pick on Carter, who was a good sport. If anything, I give him credit for sticking through the entire interview. But it speaks to a larger problem we face with our media, which is that they frequently are not well read and, more importantly, they do not realize it.

Don’t get me wrong — I’m in the media and I don’t claim any particular expertise in … anything. Not even Prince, the St. Louis Cardinals or Lutheranism, three of my main loves. I like to write about economics, sex, baseball and religion, sure, but I am all too aware of my limitations in each. My go-to line when interviewing someone is, “Explain this to me like I’m in kindergarten.” I have fun researching different topics, and I even have strong views on a few of them, but a certain humility is in order when your line of work requires neither a G.E.D. nor any particular expertise. Anyone can pick up the phone and string words together, including, somewhat improbably, me.

No liberal education

The real problem is the arrogance that goes with the ignorance. Take Kate Zernike’s 2010 attempt at an expose of the ideas that motivate tea party activists that ran in the New York Times. She wrote:

But when it comes to ideology, it has reached back to dusty bookshelves for long-dormant ideas. It has resurrected once-obscure texts by dead writers — in some cases elevating them to best-seller status — to form a kind of Tea Party canon.

Who are these obscure authors of long-dormant ideas? She points to Friedrich Hayek, for one. Yes, the same Hayek who won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1974 and died way, way back in … 1992. Whose Road To Serfdom was so obscure that it has never been out of print and was excerpted in Reader’s Digest, that obscure publication with only 17 million readers. The article doesn’t get around to actually providing any insight into these activists’ philosophy and it’s probably a good thing considering that this is what she has to say about “the rule of law”:

Ron Johnson, who entered politics through a Tea Party meeting and is now the Republican nominee for Senate in Wisconsin, asserted that the $20 billion escrow fund that the Obama administration forced BP to set up to pay damages from the Gulf of Mexico oil spill circumvented “the rule of law,” Hayek’s term for the unwritten code that prohibits the government from interfering with the pursuit of “personal ends and desires.”

Oh dear. Where to begin? How about with the fact that “rule of law” is not Hayek’s term. The concept goes back to, well, the beginning of Western Civilization and the term was popularized by a 19th century British jurist and constitutional theorist named A.V. Dicey. It’s not an unwritten code, by definition. The idea that this would be an obscure concept to someone says everything about Zernike and the team at the New York Times and precisely nothing about Ron Johnson or Hayek or that sector of citizens of the United States who retain support for the rule of law.

A few weeks ago, David Brat beat House Majority Leader Eric Cantor in a stunning upset. The media didn’t handle it well. You might say they freaked out. Among other things, reporters sounded the alarm about a phrase Brat used in his writings that, they said, suggested he was a dangerous extremist: “The government holds a monopoly on violence. Any law that we vote for is ultimately backed by the full force of our government and military.” As National Review‘s Charles C.W. Cooke noted:

“Unusual” and “eye-opening” was the New York Daily News’s petty verdict. In the Wall Street Journal, Reid Epstein insinuated darkly that the claim cast Brat as a modern-day fascist. And, for his part, Politico’s Ben White suggested that the candidate’s remarks “on Neitzsche and the government monopoly on violence don’t make a whole lot of sense.”

Unusual, eye-opening, and non-sensical, perhaps, to people who had never studied what government is. But that group shouldn’t include political reporters, who could reasonably be expected to have passing familiarity with German sociologist Max Weber’s claim that “the modern state is a compulsory association which organizes domination. It has been successful in seeking to monopolize the legitimate use of physical force as a means of domination within a territory.”

Or take the Los Angeles Times‘ David Savage, who argued just last week that the Supreme Court’s decisions under Chief Justice John Roberts “rely on well-established rights, such as freedom of speech and free exercise of religion, but extend those rights for the first time to corporations, wealthy donors and conservatives.” Perhaps it’s just poorly written. Surely a man who has been responsible for informing Californians about the Supreme Court since 1986 doesn’t actually believe that conservatives, corporations or wealthy donors were not covered by the Bill of Rights until John Roberts came along. As James Taranto of the Wall Street Journal notes, “that is as ignorant as it is tendentious.”

Back to Hiss

Hewitt begins his interviews by asking people about Alger Hiss. Hiss, of course, was the State Department official who was credibly accused of spying for the Soviet Union. Because the statute of limitations for espionage had run out, he was imprisoned after his perjury convictions. Hewitt asks the question because it’s an interesting way of determining whether someone with leftist leanings has come to terms with the fact that Communists were ensconced in high places in the U.S. government back in the day.

It’s not an easy question for some partisans. In 1996, National Security Council head Tony Lake had to withdraw from consideration as CIA chief when he let loose that he wasn’t sure about Hiss’ guilt. (Interesting side note is that Lake has been a major influence on our current president and was considered for high level positions in his administration.)

More recently, MSNBC host Karen Finney struggled mightily with the question.

But it’s almost charming to deal with people who have ideological blinders on regarding Hiss’ guilt when compared to people who are simply ignorant of who he was. Consider that this means that not only are people unfamiliar with some major details related to Joseph McCarthy, the House UnAmerican Activities Committee, and Communism in the 20th century, it also means that they have not read Whittaker Chambers’ Witness (or learned about the prothonotary warbler’s unsung role in American history).

Remember how President Reagan once quipped, “The trouble with our liberal friends is not that they are ignorant, but that they know so much that isn’t so”? Yeah, well, I think the ignorance may be turning into a problem.

Maps are hard

The problem of ignorance combined with arrogance has been well documented among the “juiceboxers,” the young and ambitious journalists who claim an expertise in explaining the news. I’ll just mention a few examples that come to mind in the map category.

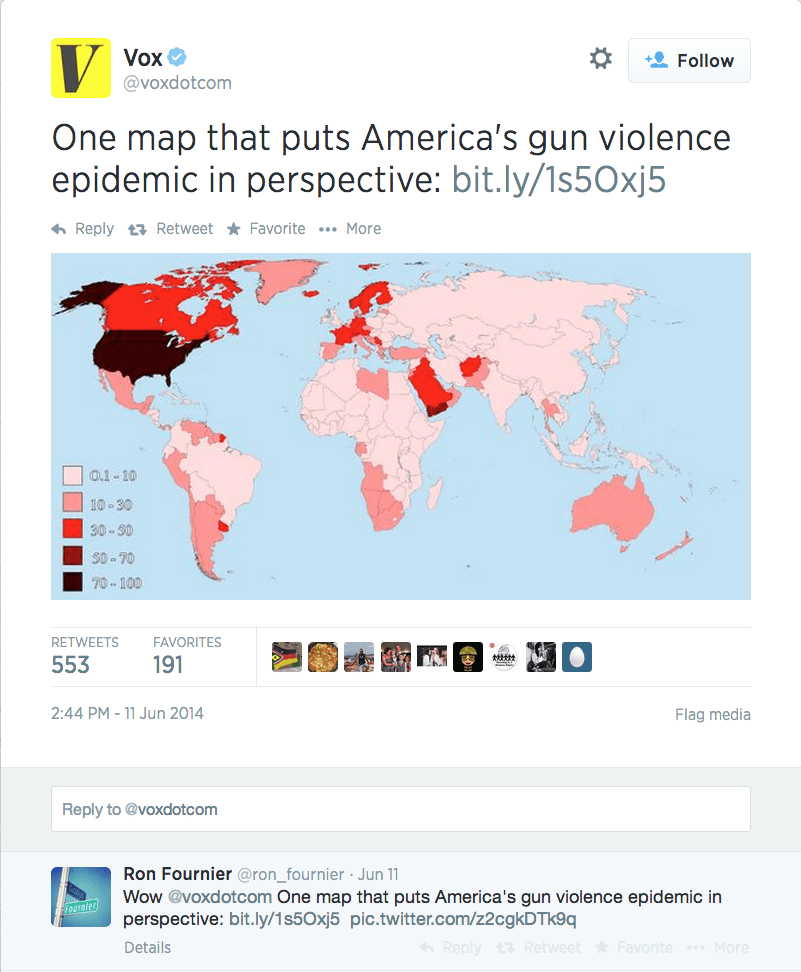

Vox is where many of them seem to be congregating, such as Zack Beauchamp, whose CV includes stints at ThinkProgress (editing an “Ideas” section) and The Daily Dish. He wrote an article that was advertised with the following tweet:

Yes, I left that first response in there on purpose. Because what National Journal‘s Ron Fournier accepted uncritically as a map of gun violence was actually a map of gun ownership rates. Which, it turns out, is not matched by gun violence rates. Over at Forbes, Chris Conover looks into all the misleading ways the article uses data and concludes:

Fellow Voxer Matt Yglesias also distributed an erroneous map recently, to hilarious effect. After an airline had wrongly suggested that Ghana has giraffes, Yglesias sent out a tweet of a map of Africa with a note, “Where giraffes live, versus where Ghana is.” Except that the map was wrong on multiple counts, causing activist Usamah Mohamed to respond, “As a Sudanese, I tell you to fix your map first before lecturing us about giraffes in Africa!”

Then Yglesias and Beauchamp joined together on a piece that purported to provide 40 maps that explain World War I. As one commenter noted:

The special category that is Matt Yglesias

Perhaps no living writer more fully embraces unabashed ignorance than Yglesias. I couldn’t begin to adequately catalogue the examples but interested readers might enjoy “Does Matthew Yglesias Ever Tire Of Being Embarrassingly Wrong About Everything?” and “Taming The Fury Of Rage: How Not To Write, Starring Slate’s Matt Yglesias.”

Everyone has their favorite example of Matt Yglesias not knowing what the heck he’s talking about. I have many, including his confusion over why the Vatican has a separate embassy from Italy and the day he found out about the Everglades.

But whatever your topic, you can find a good Yglesian whiff on it. Finance. Demeny voting. Mac vs. PC. Public Choice theory. Common figures of speech. Telecommunications policy. Hugo Chavez. The United States Senate. Black conservatives. Obamacare implementation. The U.S. Senate again. Democratic presidential primaries. Tort reform. John Edwards. Hayek and Coase. Telling the truth. Knowing about rent-seeking. The list is endless.

The media just don’t get religion

During my time at GetReligion, a site that daily analyzes how well the mainstream media handles religion news, we never lacked for content. There was the time a New York Times‘ reporter referred to the crozier, the ornate silver shepherd’s crook, carried by Pope John Paul II as a “crow’s ear.” Which of course brings to mind First Things editor Richard John Neuhaus’ stories of being interviewed:

More recently the New York Times had to run this correction:

More, more, more

And we could go on. Ignorance of global poverty and globalization, defense strategy, the entire geographic, historical and political context of Israel.

Ezra Klein wrote in 2007, “I’ve never read a compelling explanation of why the nation’s doctors and hospitals haven’t broadly adopted electronic medical records.” Mickey Kaus finds the notion so laughable that he presumes he must have just said it out of blind partisanship. But I worry about something far worse. What if he really meant it? What if, along with his Vox buddy Yglesias, he believes the other side has no good arguments because he’s never understood them or even allowed himself to read them?

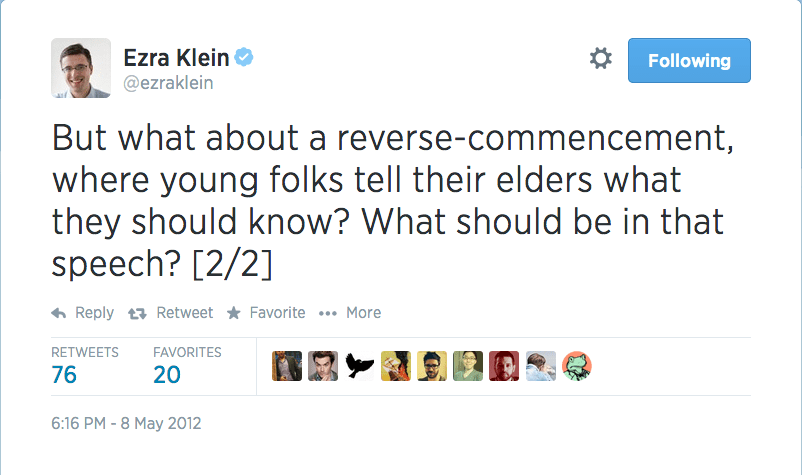

Consider the layers of ignorance and immaturity embedded in this tweet:

One internet commenter suggested a good speech might be about how “with the right connections and no relevant policy experience, you too can have a soapbox at a major newspaper.”

Carter said in his interview, “Well, I mean, I read pretty widely, I do read pretty widely on this subject.”

That was something that did not come through in his interview. It’s not something that comes through in much of what many reporters produce, whether they’re covering politics, economics, religion or history.

Clive James writes in Cultural Amnesia, “As Kingsley Amis acutely noted, the person who uses ‘disinterested’ for ‘uninterested’ is unlikely to see your article complaining about the point, because the person has never been much of a reader anyway.”

I certainly don’t expect self-reflection from Yglesias, who has shown himself impervious to gentle reproach, much less humiliating take-downs. But if Carter does read widely and is open to criticism, this could be a moment of opportunity for him. If he takes from his interview with Hewitt that he should not accept the groupthink of his media peers and should read more broadly on the areas he wishes to cover, it would serve him well.

If young reporters would humbly acknowledge that history began before Google internet searches began and even before George W. Bush came to office, this would be a success. If they would read the history, learn the arguments they dismiss reflexively as idiotic, gather even a modicum of context before pontificating, who knows what might happen?

Trust in the media has hit record lows, according to a new Gallup poll.

I can’t help but suspect this statistic would look less grim if our media were even slightly more informed about the things they act like they know so much about.