What has been will be again,

what has been done will be done again;

there is nothing new under the sun.

“Congress is trapped on the question of raising the national debt by one of its own legislative tricks — postponing disagreeable decisions until the last hours of rush to adjournment when there is no further time for deliberation and the situation is ripe for trading.”

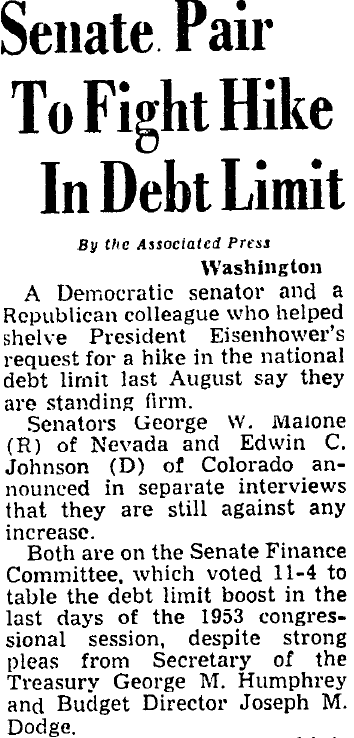

If that sounds familiar, it’s because it is. But that language isn’t from a 2013 news article about increasing the federal debt limit. It’s from a 1953 news article about President Dwight E. Eisenhower’s request to raise the debt ceiling by $15 billion, from $275 billion to $290 billion.

Everything old is new again.

Prior to 1917, when Congress first established a federal debt limit via the Second Liberty Bond Act of 1917, Congress had to authorize each individual bond issuance rather than an overall amount of debt. In addition to setting a general limit on the total amount of outstanding federal debt, the 1917 law also set limits on what types of debt could be issued. It was not until March of 1939 that Congress eliminated those limits on specific bond issues and created the general federal debt ceiling that remains in place today. Congress set that debt ceiling at $45 billion.

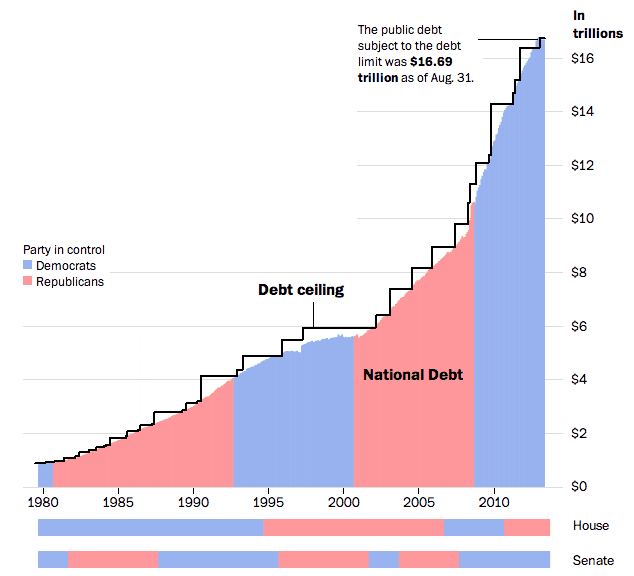

Since that limit was set in 1939, it has been amended over 90 times, or an average of more than once each year. Republican and Democratic presidents alike have asked for higher debt limits, and Republican and Democratic lawmakers alike have sworn to undertake any measures necessary to block them.

The 1953-1954 Battle

Eisenhower’s request in 1953 to increase the debt limit was not without controversy. He had just been elected, and the current debt limit of $275 billion had been in place since the end of World War II. Eisenhower used his very first State of the Union Address in February of 1953 to make a public appeal to increase the debt limit.

“The forecast presented by the outgoing administration with the fiscal year 1954 budget indicates that — before the end of the fiscal year and at the peak of demand for payments during the year — the total Government debt may approach and even exceed that limit,” Eisenhower said. “Unless budgeted deficits are checked, the momentum of past programs will force an increase of the statutory debt limit.”

Even though both chambers of Congress were controlled by Eisenhower’s Republican allies, raising the debt ceiling was no easy lift, even for one of the most highly respected combat generals in American history. Whereas Barack Obama organized communities before he sought political office, Eisenhower commanded entire armies and used them to bring Hitler to his knees.

Even though both chambers of Congress were controlled by Eisenhower’s Republican allies, raising the debt ceiling was no easy lift, even for one of the most highly respected combat generals in American history. Whereas Barack Obama organized communities before he sought political office, Eisenhower commanded entire armies and used them to bring Hitler to his knees.

Although he first mentioned the need to raise the debt ceiling in February of 1953, Eisenhower did not formally submit his request to Congress until three days before the body’s scheduled adjournment that August. It turns out that waiting until the last second in the hope of increasing negotiating leverage is a bipartisan tradition that goes back decades.

The 83rd Congress, however, would not be bullied. Led by Sen. Harry F. Byrd (D-Va.), the Senate Finance Committee rejected Eisenhower’s request by a vote of 11-4. It would take another year before Eisenhower would get his debt limit increase approved by Congress, and even then Congress only gave him an additional $6 billion, rather than the $15 billion he initially requested.

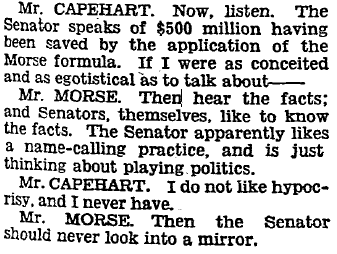

And if you think the congressional debate over the current debt limit is heated, it’s nothing compared to the 1953 floor debate between Sen. Wayne Morse of Oregon, who opposed lifting the debt ceiling, and Sen. Homer Capehart of Indiana.

“The trouble with the Senator from Indiana,” Morse said, “is that he simply does not know what he is talking about…and I am going to wrap that record around the Senator’s political neck, whenever he makes any such false statement as the one to which I referred.”

“There is nothing I would enjoy more than to have [Morse] try to wrap something around my neck,” Capehart responded. “If he tries to do it in Indiana, he will find that the people of Indiana still have left a little good common horsesense, and that they do not fall for hypocrisy.”

“There is nothing I would enjoy more than to have [Morse] try to wrap something around my neck,” Capehart responded. “If he tries to do it in Indiana, he will find that the people of Indiana still have left a little good common horsesense, and that they do not fall for hypocrisy.”

“I do not like hypocrisy, and I never have,” Capehart added.

“Then the senator should never look into a mirror,” Morse countered. Years later, Morse would refer to the portly Capehart as a “tub of rancid ignorance.”

The 1977-1978 Battle

In many respects, the battle in 1977 over Carter’s request to increase the debt was very similar to Eisenhower’s struggle in 1953. Carter had just been elected, and, like Eisenhower, was blessed with both a House and a Senate that were run by his own political party. But just as Republicans were not eager to rubber stamp Ike’s request for more debt, neither were Democrats prepared to hike the debt limit without a fight.

In September of 1977, the debt ceiling was set at $700 billion, but due to the way the law authorizing that particular limit was written, that number would fall to $400 billion on October 1 if Congress did not extend the current limit. Unsurprisingly, Congress failed to extend it. Also unsurprisingly, several senators took Carter’s request hostage and attempted to use it as a bargaining chip for negotiations over natural gas deregulation.

“With the Senate entangled in a filibuster over natural gas prices, Congress let the Friday midnight deadline slip by without passing final legislation to raise the debt ceiling,” the Associated Press reported at the time. But it wasn’t Republicans who were responsible for the filibuster. Senate Democrats led the charge and threatened to continue filibustering for weeks if necessary.

As the Associated Press noted: “‘Our intention is to continue…,’ said Sen. Howard Metzenhaum, D-Ohio, who is leading the filibuster with Sen. James Abourezk, D-S.D. ‘I guess we could continue the filibuster for another week, 10 days, maybe two weeks without much trouble.'”

They eventually relented, and a temporary debt limit increase was signed into law on October 4, three days after the statutory deadline. That was not the end of the fighting, however. Two more times — once in August of 1978 and again in April of 1979 — Congress allowed the temporary increase to expire, sending the debt limit back down to $400 billion.

The 1990 Battle

The battle between congressional Democrats and President George H. W. Bush in 1990 most resembles the wrangling today between President Obama and House Republicans: a difficult economy, mounting debt, and an impending government shutdown. Just as the current shutdown impasse appears likely to bleed into debt limit negotiations over the next several weeks, the 1990 impasse also included a shutdown fight wrapped with a debt limit crisis. But in 1990, the fight was instigated by Democrats who wished to raise taxes despite Bush’s famous “read my lips” campaign promise to block all tax increases.

In a span of just four weeks in the fall of 1990, Congress passed and President Bush signed six separate debt limit extensions. At the same time, lawmakers were embroiled in a fight over discretionary spending levels — a fight that would eventually lead to a four-day government shutdown.

“In a stunning defeat for President Bush and the leaders of both parties in Congress, the House early today rejected the new five-year, $500-billion deficit-reduction plan,” the Los Angeles Times reported on October 5, 1990.

“The White House ordered a shutdown of most of the government at midnight last night as President George Bush, in a high-stakes showdown with Congress, refused to act upon emergency legislation to temporarily continue funding for federal agencies,” Newsday wrote the next morning.

Although the government was re-opened after four days and remained open thereafter, the fighting continued for weeks, as the appropriations hostage was exchanged by congressional Democrats for the debt limit hostage. But even then, the wrangling was treated by congressional veterans as just another day at the office.

“We all know what happens over here,” Sen. Jim Sasser (D-Tenn.), the chairman of the Senate Budget Committee, said during an October 18 floor debate. “The debt limit bill comes up; the leadership puts it off until the last minute, for good reason. There are hundreds of amendments that are held out to tack onto this must-[pass] legislation. The result is that the Senate, on many occasions, works all night long for hours and passes all kinds of legislation, I submit, Mr. President, without the careful analysis that this legislation would ordinarily receive.”

In other words, hostage-taking and last-second negotiating were the rule, not the exception, when it came to things like the debt ceiling.

Congressional Democrats eventually got their way via the November 5 enactment of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, which raised income tax rates and instituted statutory PAYGO measures that would lead to sequestration if deficit targets were not met. Two years later, Bush would be tossed from office, due in large part to his now-broken “no new taxes” campaign pledge. Congress gave him the debt limit increase he wanted, but the price he paid was his presidency.

Conclusion

As Congress and President Obama come ever closer to bumping up against the debt ceiling (most experts believe Treasury will exhaust its ability to keep debt under the limit sometime in mid-October), many commentators will claim that the brinkmanship over the debt limit is unprecedented and unimaginable. The real truth is that it’s neither.

Congress and the president have fought for decades, regardless of party, over the propriety of raising the debt ceiling. Many lawmakers in years past used the debt limit as a bargaining chip, knowing that holding it up could give them leverage unachievable through other legislative means. That doesn’t mean that a fight this year is necessarily a good idea. But it is helpful to be reminded that this is not the first time our elected officials have pulled out all the stops — including shutdowns or threats of default — to achieve their policy or political goals, nor will it be the last.

There is nothing new under the sun.