Most of what you have heard about the problems in American health care is wrong. Because the experts are so consistently wrong, their remedies consistently fail, and in fact make the problems worse than they were before.

We will get into the real problems and the real solutions soon, but first it is necessary to grasp just how wrong these experts have been over the years. And when I say “these experts” I mean the exact same people that have been advising policy makers for the past forty years. They began in the 1970s and are still at it forty years later.

The list of such mistaken failures is nearly endless. What follows are just a few of the highlights in the first of a series of articles on how we got where we are in American health policy, and where we’re headed in the future.

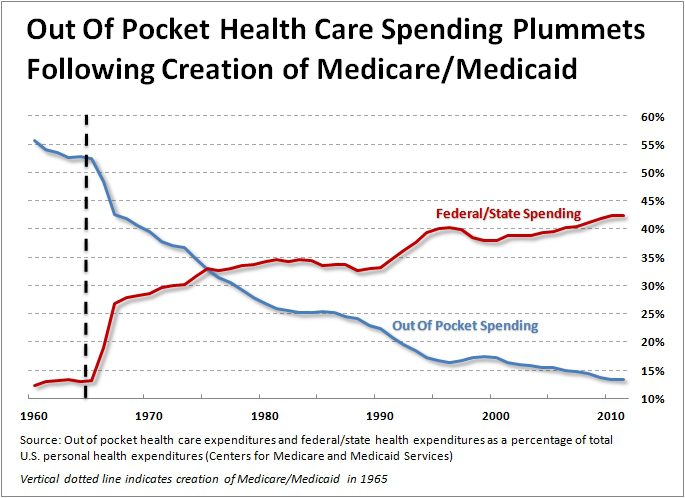

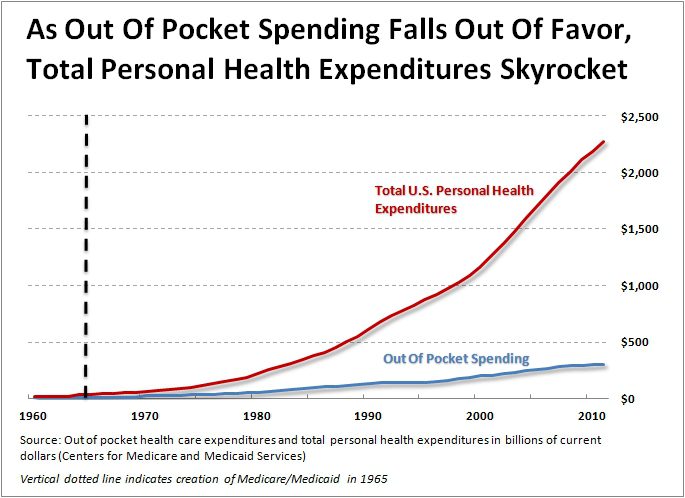

Soon after Medicare and Medicaid were enacted in 1965, the nation entered a period of enormous inflation in health care costs. This should not have been surprising. Vast amounts of new state and federal money were pumped into the health care system with no concurrent increase in the supply of services. Most of this was federal.

In 1965, state and local governments spent $3.7 billion on civilian health care, while the federal government spent only $865 million. Two years later, state and local rose 30 percent to $4.8 billion, but federal spending went up 655 percent to $6.8 billion. By 1970, state expenditures would rise to $6.6 billion, and federal spending would reach $11.2 billion over twelve times what had been spent five years earlier. The money both the states and federal governments spent on personal civilian health care went from 10.9% of total national health expenditures in 1965 to 24.1% in 1970.

The infusion of new cash into the health care system, and the fact that beneficiaries could consume services with no constraint at all, resulted in three decades of medical inflation rising at twice the rate of the economy as a whole.

In the 1970s, the experts were nearly hysterical about the rate of inflation in the health sector. Stuart Altman, now a professor at Brandeis University, was the head of HCFA. He recently reminisced — “When I was 32 years old, I became the chief regulator in this country for health care. At that point, we were spending about 7 1⁄2 percent of our GDP on health care. The prevailing wisdom was that we were spending too much, and that if we hit 8 percent, our system would collapse.”

The hysteria resulted in a raft of new laws intended to control the rate of health care spending which was increasing between 12 and 14 percent per year from 1972 on. These new laws included –

- Wage and price controls that were imposed by President Nixon in August, 1971. They were removed for most of the economy in January 1973, but retained for health care until April 30, 1974.

- Legislation creating Professional Standards Review Organizations for Medicare was enacted in 1972. These were intended to supervise physician practice to ensure appropriate treatments and lengths of stay, and restrain costs.

- The Federal HMO Act of 1973 provided seed money for HMOs that met certain federal qualifications, such as being not for profit, using community rating, providing a minimum set of benefits, and exempting HMOs from state insurance regulations on issues such as capitalization and reserves, board composition requirements, and advertising restrictions. It included a “dual choice” provision that required employers with over 25 employees to offer HMO options to their workers.

- The National Health Planning and Resources Development Act of 1974 required states to establish elaborate bureaucracies to control the growth of hospitals and other health care facilities. These agencies included Health Systems Agencies (HSAs), State Health Planning and Development Agencies (SHPDAs), Statewide Health Coordinating Councils (SHCCs), and a host of other committees and agencies. These efforts were designed to implement Certificate of Need (CON) programs, through which hospitals and other facilities that wished to make capital outlays would have to get prior approval from the agencies.

Naturally these efforts did not work particularly well. The thinking behind price controls and health planning is especially puzzling. Excess demand induced by Medicare spending had outstripped the supply of services and caused a surge in health care prices as predicted by basic economic theory. So the government response was not to lower demand or increase supply, but create a vast bureaucracy of health planning agencies to further reduce supply! Small wonder health care inflation got worse during these years.

More importantly, the whole thing whipsawed the entire health care system and caused providers to spend enormous sums to comply with the new laws and regulations – money that might have otherwise gone into patient care. We will never know how many people were damaged, perhaps even killed by this misallocation of resources.

The federal Health Planning Act was repealed in 1982, but the experts weren’t done. They had to find new ways to make a living and justify their PhDs now that they could no longer staff all the agencies created by health planning, so they came up with hospital rate setting.

They knew that with Ronald Reagan in the White House, a big federal initiative would go nowhere, so they focused on the states. This initiative was based largely on a single study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1980, “Hospital Cost Inflation under State Rate Setting Programs” by Brian Biles, Carl Schramm, and Graham Atkinson. The article concluded,

“… (T)he average annual rate of increase in hospital costs in (the six) rate-setting states has been 11.2 per cent, as compared with an average annual rate of increase of 14.3 per cent in states without such programs.”

Of course, those six states (Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Washington) started out as probably the most expensive and wasteful states in the nation. That is why they were prompted to adopt these systems in the first place. There was already plenty of fat to be trimmed, which would not be true for other states.

Indeed, a later article by the same authors in Health Affairs reported that the non-regulated states had a per capita hospital cost of $107.02 in 1972, while the states that adopted the price controls were spending $135.08 per person. Further, these costs were spread over a much larger hospitalized population in the non-regulated states, which had an admissions rate of 152.8 per thousand in 1972, compared to 131.1 per thousand in the states that adopted regulations.

Usually in research if there is a self-selected sample being studied, the researchers look to see what might distinguish the sample from the rest of the population and adjust their findings accordingly. Not so in health policy. Health policy advocates are so eager to push their preferred remedies that they ignore what should be standard techniques of research.

The study mentioned above completely overlooked many pertinent differences between the six regulated states and the forty-five (including DC) non-regulated areas. Obvious differences include that the six states tended to be no-growth or low-growth states, so they had little need for new hospital construction. They also tend to be high Medicaid enrollment states, but also with higher average incomes than the non-regulated states. Other possible differences that would have been worth exploring include the relative percentage of uninsured, the ratio of teaching hospitals, the availability of non-hospital alternatives such as home health services or free standing surgical services, and the presence of for-profit hospitals. All of these differences could have had a profound effect on the viability of hospital rate setting in the various states but none were even considered.

As it was, what the research discovered was that after 13 years of experience:

- The high-cost states remained high cost.

- These states began with lower rates of admissions, and ended with lower rates of admissions.

- They began with lower operating margins and ended with lower operating margins.

Yet somehow the researchers concluded that hospitals in the regulated states were “more efficient” than those in the non-regulated states, though it would seem that having fewer admissions at higher costs while maintaining low profit margins would be a slam dunk argument that these regulated hospitals were anything but more efficient.

Such one-sided research was persuasive enough to the “health policy community” that 30 states ended up adopting similar rate setting programs during the 1980s.

In 1997 Health Affairs published another article with a somewhat different tone, titled “Tracking the Demise of State Hospital Rate Setting” by John McDonough, now a prominent professor of public health at Harvard. The article said, “Now, in the mid-1990s, state rate stetting is nearly gone; most major systems have been deregulated during the last ten years.” (Ultimately these systems were repealed by every state but Maryland.) The article explained that the growing managed care companies thought they could negotiate lower hospital rates than were available through price-controls, and that the regulators themselves agreed their rules were “incomprehensible.”

Not mentioned by the author, but fairly obvious, was the reality that was evident to anyone who could see the full picture: once state government becomes responsible for setting prices, it also becomes responsible for ensuring the solvency of the facilities. Inefficient facilities are protected from failure, and any decision to close a hospital becomes a political, not an economic, one. A threatened facility can generate enough political support to keep its doors open, even when it makes no economic sense to do so.

Once again an idea of central planning was tried and failed miserably, at the cost of many billions of dollars and who knows how many lives lost or destroyed. All on an idea that was poorly thought through in the first place. And as you’ll see, within the realm of health policy, this was only the beginning.