In 2018, Nellie Bowles wrote a scathing profile of Jordan Peterson for The New York Times, depicting him as a swindler and the patron saint of incels. In 2021, Bowles indirectly apologized. Not mentioning Peterson by name, she lamented acknowledged all the previous harm caused by her addiction to going viral.

At the Times, she would write stories that she called “kills,” and her measure of success was how loud the Twitter mob roared in response. This approach made her famous. She also felt it was making her a sociopath. So she left the Times and decided to be more cautious with her words.

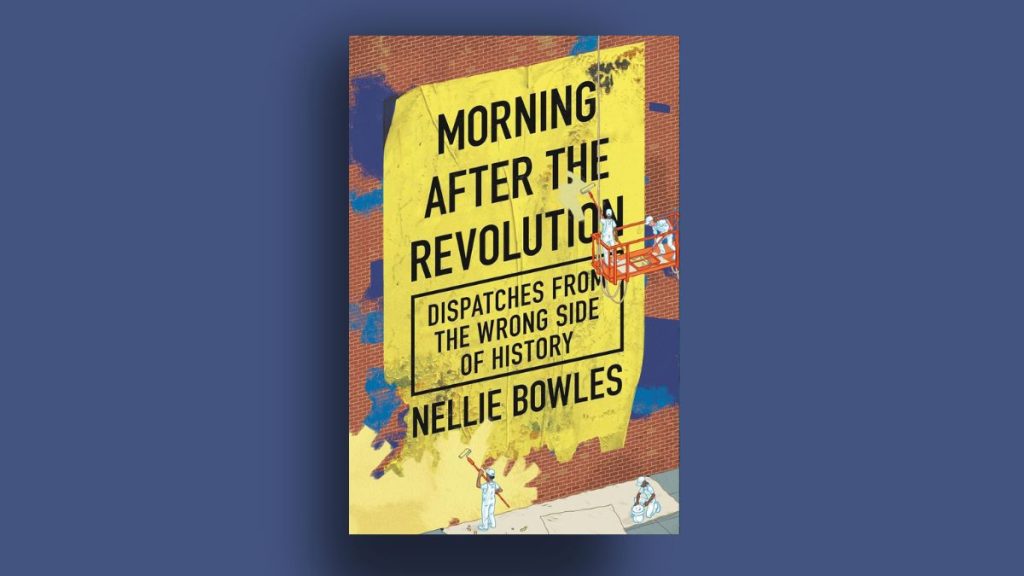

Her new essay collection, Morning After the Revolution, has few “kills,” but, unfortunately, lacks conviction as well. Reflecting on the madness of the past few years — BLM, CHAZ and abolish the police, trans activism — Bowles rarely provides insight, instead recapping widely covered events with some humorous remarks and vivid reporting mixed in. While her criticism of Peterson was mean-spirited but clear — she was a foot soldier of the progressive left — her new persona is a “hesitating moderate” willing to make fun of anyone.

In the format of her satirical weekly news roundups, this positioning works well. But that same tone doesn’t translate well to a book-length review of the hottest issues of the past five years. By avoiding principled stands in favor of sarcasm, Bowles adds little to the conversation besides entertainment.

When Johns Hopkins defines described a lesbian as “a non-man attracted to non-men,” she can joke, “Yep, that’s me,” but she does not follow that with a defense of her position on gender and sexuality. Her analysis falls victim to cynicism and the fallacy of moderation.

The Fallacy of Moderation

Aristotle suggested in the Nicomachean Ethics that a virtue is the golden mean between two vices. Between cowardice and recklessness lies courage. Between shyness and shamelessness lies modesty. This is a compelling ethical theory, but applying this principle in all situations — believing that truth is always found at the midpoint — is fallacious.

For example, if I say the sky is red and you say it’s yellow, that doesn’t mean it’s orange. By the same token, if one side is pro-LGBTQIA+ and the other side supports traditional marriage, that doesn’t make pro-LGB correct. On fundamental questions like, “Are all white people racist?” or “Are trans women and biological women the same?” humans need and deserve principled, thorough responses, not simply a compromise between the rhetoric of the extreme left and right. Otherwise, your position depends on the whims of radicals.

Despite this, Bowles, a married lesbian, is hesitant when examining whether the trans movement is a logical extension of the gay rights movement or a hijacking of it. In a brief aside, she admits that she had a “tomboy” phase and may well have undergone hormone therapy were she a child today.

She worries that trans activists claiming that biological males would have no advantage in sports — an obvious falsehood — will undermine something that seemed already settled: that gay marriage should be legal. She joked: “I was feeling, honestly, a little crazed about it all — these doctors are sterilizing young homosexual children was how I sounded at social gatherings. Everyone is eliminating women was something I would attempt to discuss in very inappropriate situations.

Then her Reform Jewish synagogue announced that the next “Tot Shabbat” — the children’s service — would feature a drag queen story hour. Bowles initially panicked, but when the day arrived, the drag queen ended up delivering a “very Jewish children's service.” Bowles concludes, “Our daughter loved it and so did I,” because after all, she remembers “being at drag bars as a teenager and how amazingly fun it was.” On the most controversial issue of our time, Bowles’ conclusion is indifferent. very Casual to an Excessive Degree

When Bowles’ book was first announced,

the statement to the media Struggle Sessions called it , evoking the repressive Soviet regime (and implying parallels with Bowles’ former employer, The New York Times). But Bowles turns out to be no bomb-thrower, so perhaps it makes sense that the title ended up beingMorning After the Revolution , implying that the BLM riots, CHAZ, and TERF/trans showdowns have more in common with a one-night stand or binge drinking than a police state. The “morning after” can be a little embarrassing upon reflection, but it’s hardly cause for shock and alarm.This same lax attitude holds for Bowles’ opinion of her own contributions to cancel culture. Here again, as an NYT darling-turned-outcast, one might expect some gory detail or hard-earned wisdom. Instead, the chapter “The Joy of Canceling” opens by describing the “pleasure” of canceling someone:

Then, instead of meditating on the perverse incentives of cancel culture and what she learned, she merely says she lost her taste for blood once she fell in love. Bowles would end up marrying Bari Weiss, who was an editor for The New York Times until she wrote

To do a cancellation is a very warm, social thing. It has the energy of a potluck. Everyone brings what they can, and everyone is impressed by the creativity of their friends.

a viral resignation letter accusing the Times of illiberalism, antisemitism, and a culture that viciously punished Wrongthink. Bowles left quietly a few months later. Bowles admits that she was never canceled the way Bari was. One wonders whether it’s because she was too canny to be canceled or merely too milquetoast to be problematic. As the saying goes, it’s good to have enemies: it means you’ve stood up for something, at some time in your life. Bowles seems to have few.

What Could Have Been

Morning After the Revolution

is plagued by all the books it could have been. There could have been Nellie Bowles, bona fide counter-elite: a product of San Francisco private schools, Columbia University, and The New York Times, now a columnist at The Free Press and critic of the culture she came from. Or Nellie Bowles, award-winning reporter, here to give the definitive retrospective on the insanity of 2020 bolstered with on-the-ground observations. Or Nellie Bowles, Hillary Clinton-supporting lesbian who finds herself now feted by the right-wingers in her comments section, trying to make sense of our new coalitions.

Bowles does none of this. Instead, we have a book of outdated reporting — we already know BLM was a front, DiAngelo is a race hustler, and San Francisco is a hellhole — with wishy-washy analysis, punctuated with some blessed respites of humor. Bowles’ refusal to make normative judgements makes her arguments tantalizing but ultimately unsatisfying because she never stakes out a position, never steps into the arena.

Funnily enough, Jordan Peterson

just this challenge. In his opinion, growing up means moving from being naive to being cynical to having courage. Being cynical is better than being naive because at least you're not being tricked, but having courage is even better: standing up for something and aiming higher rather than just tearing things down. talks about Morning After the Revolution

seems like a work in progress, a disappointed progressive using irony as a shield until she regains her bearings. Bowles is intelligent, clever, and talented. Having a bit more courage and strong belief (may I say, a bit more of Peterson's qualities?) would help her a lot. Cancel culture pack leader Nellie Bowles’ new persona is a ‘hemming-and-hawing moderate’ willing to make jokes about anyone.